I first found out about short bowel syndrome (SBS) from the doctor telling me I had it while I lay in hospital. Rewinding back a few years, I had been getting unexplained stomach pains since I was 15. A lot of doctors didn’t know what was causing them, and my pain was largely dismissed. Things changed in 2019 when I had an episode of really bad pain, and went to the hospital near where I live in Scotland. On being told I had SBS I found it difficult to process. I underwent a number of emergency surgeries, and it felt like almost overnight I had to suddenly deal with a big and long-term health problem. On being told I had SBS I found it difficult to process.

When my doctors first explained artificial nutrition, all I could think was, is that even possible? Understanding how parenteral nutrition works and how it keeps you alive was all part of my ‘new normal’. My family and I had a lot of questions about how best I could recover, but the answers we got from the healthcare team all felt very unpredictable – it felt like we were always told “it depends”, “maybe”, “potentially”.

It wasn’t until I’d been in hospital for over a month that I realised my parenteral nutrition was potentially permanent. I had assumed that it was just for while I was in hospital, not for life. That realisation was another hugely overwhelming moment. My training on how to set up my own parenteral nutrition was comprehensive, and I felt well-versed before I left the hospital on the practical parts. But the bigger picture still terrified me, and I found it incredibly difficult to process.

This all happened at the start of my bachelor’s degree in criminology at Stirling University. I remember my doctors assumed I would quit school and move back home to Amsterdam. They could see the bigger picture, but I hadn’t yet realised just how much my life needed to change.

I was thankful to be out of hospital, but I found it disconcerting to be connected to my feed 12 hours a day whilst also being surrounded by busy university students. If anything, I felt even more restricted and like an outsider – during those 12 hours I was afraid to leave my room, and I couldn’t go for dinner with people as I couldn’t eat solid foods for a year and a half.

In a weird way, when Covid-19 hit things became easier for me. I didn’t have the energy to walk for more than a few minutes at a time, and I was finding it hard to go to class and be social. The transition to more of an online life was a blessing in disguise for me because it meant I was able to continue my studying at home and be connected while I was listening to a lecture. The restrictions also meant that everyone was excused from being social, so I felt less like I was missing out.

Apart from my education, another huge aspect of my life which has permanently changed is my ability to travel. I come from a very international family – we’re scattered all over – and so travelling has always been an important part of my life. As I was taught about parenteral nutrition, I kept thinking how can I continue to see my family that live abroad? One bag of parenteral nutrition is 4L and has to be cooled, and I need one for every night, on top of a pump, and all other equipment.

Understanding how parenteral nutrition works and how it keeps you alive was all part of my ‘new normal’.

The homecare provider service was really good in the beginning – they delivered to airports and they recognised that artificial nutrition shouldn’t dictate my life. However, more recently I’ve had issues with timely deliveries and it can feel like an uphill battle to sort all the logistics necessary just to visit my parents in Amsterdam. I don’t feel heard by them, nor taken seriously. I think communication is really key, and it would be great if this was better between my doctors, my homecare provider, and me.

I’m yet to meet another young person who’s on artificial nutrition, which can be very isolating. This also ties into having to re-explain my situation over and over to various doctors, teachers, employers… which can feel triggering, and I often don’t feel like I’m in the right headspace to do so. I’ve definitely seen an impact on my mental health – both because of the physical struggles but also the isolation.

I feel as though the mental health hasn’t been given enough focus in my care. On the medical team there’s a pharmacist, nutritionist, dietitian, surgeon – but no one is there that’s dedicated to your mental health. I firmly believe that having a psychologist on-hand would make such a positive difference to any low mood or anxiety felt as a result of the physical trauma.

I’ve always loved food. You don’t realise until something is taken away how much it’s in your life – all special occasions are oriented around food, particularly Christmas. My family were all very supportive and restructured our celebrations to take the focus away from food, as it was too triggering for me. I felt very low and advocated hard to have surgery so that I’d be able to eat food. I’m so grateful that I was able to do this, and since then food has become even more of a passion of mine. Having not been able to have it for a long time, I now make a really big effort with my cooking – I love experimenting with different flavours and techniques. My favourite food is sushi… it’s hard to make but that’s what makes it fun!

My medical team have been incredible overall, and I feel very lucky to feel safe with them. They take the time to talk to me, explain things clearly and give me space to talk. However sometimes I don’t feel like they really hear me. I don’t think it’s for them to say my life is good. My health may be stable on paper, but I don’t think that equates to quality of life. If I could ask healthcare professionals to be aware of one thing it would be to actively listen. I can’t emphasise enough how important this is – to feel like I’m receiving personalised, person -centred care.

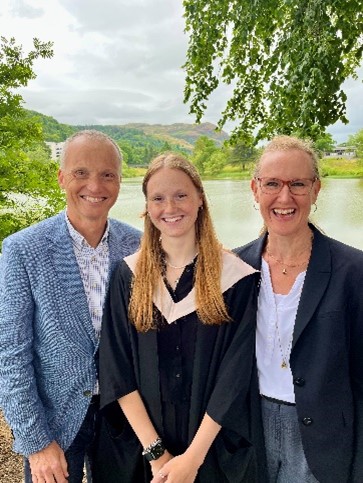

Over the past four years, I’ve definitely adapted to artificial nutrition. In the beginning, I saw it as forced upon me. Now I can understand that it’s keeping me alive, and I’m grateful for what it’s allowed me to do. Despite my doctors thinking I would move back home to Amsterdam and the unpredictability my condition continues to bring, I managed to complete my degree and I feel really proud of what I’ve achieved. It definitely still brings its difficulties and restrictions, but I’m trying to adopt a more positive outlook as best I can.